July 19, 2017

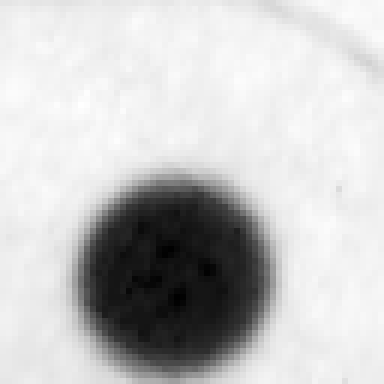

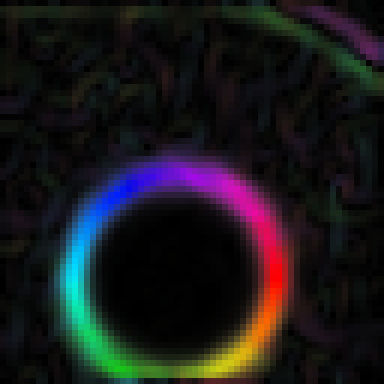

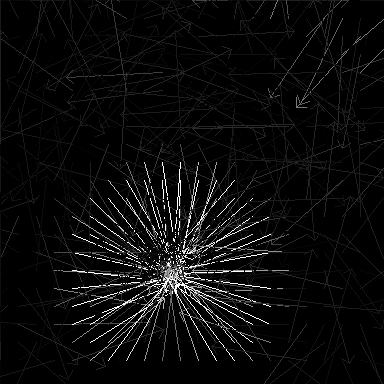

## Intro Last week at work I was faced with the problem of accurately detecting the center of a circle in an image. A classic computer vision problem, but with some confounding issues: * The image can be noisy and blurry * The brightness of the dot and surroundings can vary * The circle can be partly obscured To my help I knew there was exactly one circle in the image, and I knew the radius of it. Some example images:  I ended up inventing a new circle detection algorithm which handles all the above issues and with robustness and accuracy. It can also be generalized to handle multiple circles of unknown radii. ## The algorithm Let's start off with the simple case of detecting the center of exactly one circle of a known radius, *R*. A few observations helps us: * The edge of the circle is always *R* pixels away from the center * The gradient of the edge is pointing towards the center of the circle * The gradient of the image is strongest at the circle edge Together this leads us to the algorithm: * Calculate the gradient of the image * For each pixel, follow the gradient *R* pixels (with subpixel accuracy) * Vote for this being the center of the image * The weight of the vote is proportional to the norm of the gradient * Use a robust, weighted centroid of the votes to get the circle center Simple, right? Let's go through these steps one by one: ## The gradient If one thinks of a grayscale image as a heightmap, then the gradient is the slope of the landscape. In this analogy, the edge of a dark circle on a bright background is like the inside of a crater rim:  Now consider stumbling around in such a landscape blind-folded (don't try this). If you find a steep slope, it is likely the inside of the crater rim. If you follow the slope downhill, you are likely to find the crater center after walking *R* meters (where *R* is radius of the crater). If you find a gentle slope, it could be the part of the crater or just some small bump outside or inside it. In other words, a steep slope is more likely to be on the crater rim. This helps illustrate the weighting strategy in the algorithm: the stronger the gradient, the more likely it is the circle edge. You can calculate the image gradient using, for instance, a [Sobel filter](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sobel_operator). For my purposes, a kernel size of 5 worked well. Here is an example:    ## Collecting votes For each pixel in the image, calculate the gradient. If it is zero, ignore this pixel. If not, move R pixels along the gradient and save that position as a "vote" with a weight proportional to the norm of the gradient. Note that the position can be a fractional pixel, so don't snap it to integer coordinates!   ## Tallying votes Most strong votes will come from the actual circle edge, but there will also be quite a few bad votes from noisy parts of the image. Thus, we don't want to simply take the average of all the votes, nor even a weighted average. Instead, we want to take a [*robust*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robust_regression) weighted average – i.e. we find an average that ignores outliers. There are many ways you can accomplish this, but a very simple yet effective strategy is [trimming](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Least_trimmed_squares). This means we find a starting guess for the circle center and then we iteratively compute a new center using only the points within a certain distance to our current center. But what should be the starting guess? The guess must be close enough to the circle center, or the trimming iterations won't converge. I opted for a very simple strategy: bucketing. I divide the image into coarse buckets, and collect weighted votes in each bucket. The bucket with most votes is used as a starting guess. Here is the whole process, from votes to the final circle center:  ## Pseudo-code ~~~ # Find the center of a circle with radius *R*: function circle_center(image, R) -> Point: let gradient = calc_gradient(image, KERNEL_SIZE) var votes = vector<Point>::new() var weights = vector